By Shala Nicely, LPC and Caitlin Pinciotti, PhD, Assistant Professor at Baylor College of Medicine

I’m thrilled to be joined by Dr. Caitlin Pinciotti of Baylor College of Medicine for this Aha! Moments blog post about post-traumatic OCD, where we’re going to cover:

I’m thrilled to be joined by Dr. Caitlin Pinciotti of Baylor College of Medicine for this Aha! Moments blog post about post-traumatic OCD, where we’re going to cover:

- Shala’s recent personal experience with PTSD, OCD, and a combination of the two: post-traumatic OCD

- The characteristics of post-traumatic OCD

- The research about OCD, trauma, and post-traumatic OCD

- The treatment for post-traumatic OCD

- Things we hope you remember during your treatment journey

- Where to find treatment for post-traumatic OCD and additional resources

At the bottom of the post is also

Time Travel

In May of 2020, I (Shala) moved into a new house in an urban neighborhood that was under construction. The house to my right was completed, but all the other houses around mine were in various stages of being built.

One day I was walking to the mailboxes on the under-construction street behind my house (with no sidewalk) with my two little dogs. Suddenly, a huge forklift came around the corner and started speeding down the street….backwards. The forklift driver was looking forwards—not where he was going—and he was heading straight for Bella, Peanut, and me. He was driving so quickly that by the time I realized that he was going to hit us, I didn’t know how to get both the dogs and me out of his way, and I froze in my tracks. All I remember is that I screamed bloody murder and somehow the driver heard me and stopped just in time.

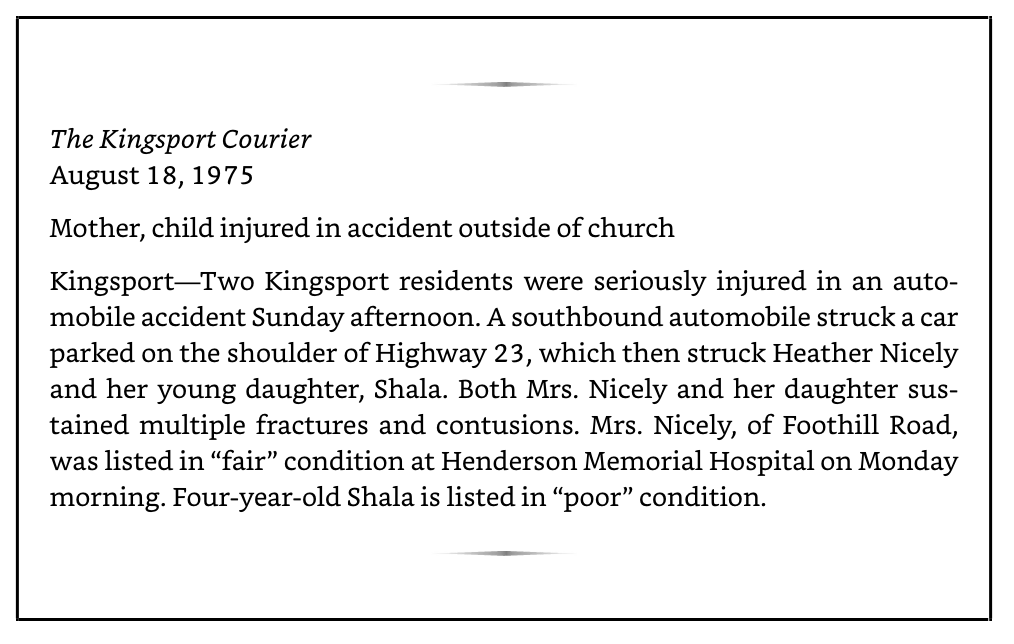

From the outside, it seemed that catastrophe had been averted. On the inside, however, that incident caused my brain to time travel, and a forklift barreling toward my fur kids and me transformed into The Accident that had happened to my mother and me forty-five years earlier*:

*Excerpt from Is Fred in the Refrigerator? Taming OCD and Reclaiming My Life, page 6.

Given time, my brain might have been able to self-correct and recognize that the forklift incident wasn’t a big deal, and that it was 2020, not 1975, and that I was as safe as anyone could reasonably expect to be. But May 2020 was the beginning of the pandemic, and I was stuck at home, surrounded almost daily by construction equipment that was the same scale to me as an adult that a car had been to me when I was four years old.

And it was more than my brain could take.

OCD Symptoms with a Twist

In the weeks and months that followed the forklift incident, I started exhibiting the classic symptoms of PTSD for the first time in my life, including flashbacks and extreme feelings of distress and physiological panic-like reactions whenever the construction equipment was near my house; feelings that the memories of my childhood trauma were there, but I couldn’t touch them; a renewal and amplification of my OCD’s past belief that the world was a very dangerous place; as well as hypervigilance and disturbed sleep.

In the weeks and months that followed the forklift incident, I started exhibiting the classic symptoms of PTSD for the first time in my life, including flashbacks and extreme feelings of distress and physiological panic-like reactions whenever the construction equipment was near my house; feelings that the memories of my childhood trauma were there, but I couldn’t touch them; a renewal and amplification of my OCD’s past belief that the world was a very dangerous place; as well as hypervigilance and disturbed sleep.

I also started exhibiting a recurrence of some of my OCD symptoms, but they had a bit of a different flavor this time. It wasn’t the typical intrusive thoughts of “what if something bad is going to happen?” Instead, the thoughts were “something bad IS going to happen, I just don’t know when it’s going to be.” In addition, my brain seemed to give me very specific rationalizations for why I needed to do these compulsions, including:

- Checking doors at my house repeatedly, including long periods of staring, touching, and locking and relocking the deadbolts, because the construction equipment was always “out there” and I had to make sure it couldn’t get “in here.”

- Getting lost in what I call “flashforwards.” These are intrusive thoughts of potential future violent harm, such as someone driving by my house and shooting me while I’m outside. The accompanying compulsion is for the rest of the world to recede while I explore potential outcomes that would prepare me for the future trauma, including figuring out how bad that situation was going to be (where would the bullet go? would I pass out or die instantly? would Bella be with me?), who was going to help me/us (would a neighbor help? would the EMS get here in time? who would help Bella?), and would I be able to handle the situation (and the answer would always be “no”).

- Checking repeatedly while driving to ensure I wasn’t hitting someone, because I wouldn’t be able to live with the trauma of traumatizing someone else.

- Participating in people pleasing rituals on steroids: doing whatever it took to ensure people liked me, as people who didn’t like me might be more likely to somehow attack me.

It was clear to me I had developed PTSD (with delayed expression) and that my OCD was flaring up as a result. But what I also realized as the weeks went on was that the two disorders had also merged, and I had post-traumatic OCD.

When PTSD and OCD Intertwine: Post-traumatic OCD

The symptoms of PTSD are maintained through avoidance of traumatic triggers or memories of the trauma, as our brains think that if we can avoid, then we can keep ourselves from being retraumatized in the future. The symptoms of OCD are maintained by doing compulsions to bring down anxiety. Post-traumatic OCD (PTOCD) occurs when OCD compulsions are used by the PTSD for the purpose of facilitating avoidance, which also brings down distress and anxiety.

So how do you spot post-traumatic OCD? While there unfortunately aren’t any official diagnostic criteria, here are some clues that PTOCD may be present:

So how do you spot post-traumatic OCD? While there unfortunately aren’t any official diagnostic criteria, here are some clues that PTOCD may be present:

- Having either untreated PTSD or trauma as well as OCD (I’ve seen several instances of PTOCD in people who wouldn’t meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD but who do have a history of some type of trauma)

- Trying to do ERP on its own causes a severe emotional reaction that’s beyond the expected increase in anxiety

- Habituation to the OCD triggers through stand-alone ERP happens very slowly (if at all)

- The intrusive thoughts in OCD may have a seemingly more plausible connection (albeit still loose) to the compulsions being performed (as in my examples above) than is typical with OCD on its own

- The intrusive thoughts attributed to OCD are accompanied by some firmly held beliefs called stuck points about self, others, or life, such as “when bad things happen, it’s my fault” or “people cannot be trusted” or “I have to be nice to other people or they will hurt me.” The presence of these beliefs may lead to a shift in the focus of the uncertainty in the OCD symptoms: instead of wondering if something bad is going to happen, the “something bad happening” is taken as a given and the uncertainty becomes about when or where it might occur.

- Doing ERP by itself or trauma treatment on its own leads to only partial symptom relief and/or to relapse.

Research about Post-traumatic OCD

Recent research is helping us to better understand PTOCD, including how often it occurs, what it looks like, and how it impacts people. For example, we know that OCD that develops after PTSD tends to be more severe and onset later in life – this makes sense, as it is likely that the OCD developed in response to trauma and PTSD (Fontenelle et al., 2012). PTOCD is also associated with a higher risk for co-occurring agoraphobia, panic disorder, and impulse control disorders.

Recent research is helping us to better understand PTOCD, including how often it occurs, what it looks like, and how it impacts people. For example, we know that OCD that develops after PTSD tends to be more severe and onset later in life – this makes sense, as it is likely that the OCD developed in response to trauma and PTSD (Fontenelle et al., 2012). PTOCD is also associated with a higher risk for co-occurring agoraphobia, panic disorder, and impulse control disorders.

Given that the majority of people in the general population are likely to experience a potentially traumatic event at some point in their life, it should be no surprise that many people with OCD have experienced trauma (Gershuny et al., 2008). However, it may be surprising to know that 44% of adults with severe OCD in one study felt that their OCD was directly caused by some sort of very stressful or traumatic experience (Pinciotti & Fisher, 2022). Among people with OCD who have also experienced trauma, nearly 86% believe that their OCD and trauma are linked in some way, and 67% believe that their OCD behaviors help them cope with their trauma-related experiences (Pinciotti & Wadsworth, 2023). When asked to describe in their own words how they believe their OCD and trauma are linked, many people with OCD described feeling as though the trauma either caused their OCD or made their existing OCD much worse, that the content of their OCD was related to their trauma, that OCD symptoms were used to cope with past trauma or prevent future trauma, and that trauma-related symptoms and OCD symptoms tended to rise and fall in tandem (Pinciotti & Wadsworth, 2023).

To participate in ongoing research about OCD and trauma, take the National OCD Survey.

Treatment for Post-traumatic OCD

Because OCD and PTSD are so strongly intertwined in people who have post-traumatic OCD, treating just one disorder at a time typically does not provide enough relief. This is likely because focusing on only one set of symptoms (OCD or PTSD) does not consider the whole picture, and symptoms of the other disorder are likely to pop up in treatment regardless. In fact, some people may notice that decreases in symptoms of one disorder might lead to increases in symptoms of the other disorder, almost like the secondary symptoms are taking their place because the root issue has not been adequately addressed (Gershuny et al., 2003). This is why many OCD and PTSD providers recommend treating both sets of symptoms simultaneously, such as by combining evidence-based OCD treatment (e.g., ERP or exposure and response prevention) with evidence-based PTSD treatment (prolonged exposure, PE, or cognitive processing therapy, CPT). In situations where someone experienced prolonged trauma, such as prolonged childhood abuse over many years, it might also be helpful to integrate components of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) for PTSD to provide more support for heightened emotional distress and interpersonal concerns.

In a nutshell, here is how combined PTSD and OCD treatment works to alleviate symptoms:

In a nutshell, here is how combined PTSD and OCD treatment works to alleviate symptoms:

- Prolonged exposure, or PE, helps you remember and process the trauma and be in the presence of triggers without reliving the trauma. Doing PE helps your mind learn that it doesn’t have to avoid memories of the traumatic event or triggers that remind you of it to keep you safe because it has learned that you are safe in the present moment. This learning makes it easier to let go of compulsions that have been helping you avoid the memories and triggers. When I (Shala) did PE, I listened to a recording of myself talking about my memories of The Accident (imaginal exposure) over and over again until they didn’t cause much of an emotional reaction. I also did in vivo exposure to triggers, such as going up to parked construction equipment and putting my hands on it.

- Cognitive processing therapy, or CPT, helps you to realize that the “stuck points” (beliefs about yourself, others, or the world that have been impacted by trauma) that were created in your mind after the traumatic event and which have been guiding your actions post-trauma are no longer helpful for you. For instance, one of my stuck points was “If I am careful and vigilant enough then I can prevent bad things from happening.” Through CPT, I challenged that belief and came up with a more helpful alternative: “While sometimes it can be helpful to be careful (but not always), vigilance just exacerbates my PTSD and neither vigilance nor being careful will ensure bad things don’t happen.” After challenging beliefs and creating new ones, the next step is to start taking actions that support the new beliefs. For me, an example of new behavior was standing close to construction sites and watching them work while not acting in a hypervigilant “oh my gosh are they going to hit me?” manner. It’s acting as though the stuck points are true through PTSD avoidance and/or OCD compulsions that maintains both disorders and PTOCD.

- Simultaneously, I also worked on exposure and response prevention therapy, or ERP, focusing, for example, on the response prevention of trying to reduce the door checking I was doing in my house. The door checking had been reinforced by the avoidance of the memories of The Accident (the memories felt dangerous, so the world must also be dangerous) and by the fact that I had been acting after the incident with the forklift as though the stuck points were useful. As I did PE and learned the memories weren’t dangerous and then did CPT and learned the stuck points weren’t helpful, then it was easier over time to reduce or eliminate the OCD compulsions.

- You don’t have to do both PE and CPT, but I have found in my own therapy and in my work with clients that often we can benefit from both since they target different aspects of how the trauma presents and maintains the PTOCD.

Many published examples exist which describe how people with OCD and PTSD benefited a great deal from a concurrent or combined treatment approach (e.g., Pinciotti, 2023; Van Kirk et al., 2018), and a recent study reported significant improvement in eight individuals with severe OCD and PTSD following concurrent ERP and PE (Pinciotti et al., 2022).

What I’ve learned from own experience with PTOCD is that maintenance of my recovery is an ongoing process. If I have an OCD lapse, it’s almost always PTOCD and associated with a major PTSD trigger. For instance, I struggled with PTOCD symptoms after I was rear-ended as part of a hit-and-run and when the city spent four days paving my street, parking all the giant paving equipment across from my house each evening. During these episodes, I worked to use my skills to manage the symptoms and get my OCD back in check: I met with my therapist after the car accident and processed what happened; I purposely stood by the parked paving equipment and took selfies (that’s me with a milling machine that eats asphalt!); and I woke up each day saying “hello, paving equipment, I can handle that you’re here this morning” to show my PTOCD I could handle these triggers and to empower myself in the face of the flare up.

What I’ve learned from own experience with PTOCD is that maintenance of my recovery is an ongoing process. If I have an OCD lapse, it’s almost always PTOCD and associated with a major PTSD trigger. For instance, I struggled with PTOCD symptoms after I was rear-ended as part of a hit-and-run and when the city spent four days paving my street, parking all the giant paving equipment across from my house each evening. During these episodes, I worked to use my skills to manage the symptoms and get my OCD back in check: I met with my therapist after the car accident and processed what happened; I purposely stood by the parked paving equipment and took selfies (that’s me with a milling machine that eats asphalt!); and I woke up each day saying “hello, paving equipment, I can handle that you’re here this morning” to show my PTOCD I could handle these triggers and to empower myself in the face of the flare up.

But I also try to keep my expectations realistic—an intertwined flare-up of PTSD and OCD can often take longer to manage than OCD on its own … and that’s OK. Each time I work through a PTOCD flare-up, my recovery gets stronger. And the more I can act as though my new beliefs created during CPT are true as I go through day-to-day life, the stronger and stronger my PTOCD recovery becomes.

Things to Remember about PTOCD

PTOCD is treatable, but as you’ve seen in this post, working on recovery is a little bit of different than doing so for either PTSD/trauma or OCD alone. We hope you find the following tips helpful as you work on your PTOCD recovery .

- Work with an experienced therapist: Try to find a therapist with experience in treating both PTSD with evidence-based treatment and OCD with ERP, and you can find a link to a list of therapists Dr. Pinciotti has compiled below.

- Know therapy can take time: In my own personal experience of getting treatment for PTOCD and in my experience treating others, it can take longer to treat PTOCD. And this makes sense, as you’re treating two disorders, not just one. Because PTSD/trauma and OCD are propping each other up, OCD compulsions may seem stickier until you can work on loosening some of the trauma stuck points using CPT and/or until you’ve been able to remember the traumatic event without reliving it using PE. If the OCD exposure work seems overwhelming due to the merged nature of the disorder, I might take a graduated approach to working to stop compulsions by starting with easier triggers and then working my way up the hierarchy.

- Be self-compassionate: It’s challenging to work on OCD or PTSD/trauma, not to mention working on them together! So give yourself a break. A big one. See Kimberley Quinlan’s amazing workbook for specific exercises you can do to incorporate self-compassion into your treatment program.

- Don’t give up. Having a merged case of two disorders can make you feel like you can’t get better, but that isn’t true! OCD and PTSD/trauma want you to continue avoiding to keep you safe, but in the long-run, avoidance can keep you from the people, events, and things that bring meaning to your life. So know that the process may be slow and that OCD and PTSD/trauma are likely to be stubborn in their beliefs and actions as you get started, but keep self-compassionately plugging away anyway, so that you can tame PTOCD and reclaim your life.

PTOCD Treatment Providers and Additional Resources

Dr. Pinciotti has compiled a list of providers who treat OCD and PTSD with evidence-based treatment on her resources page, which also includes handouts about safety behaviors in OCD and PTSD, evidence-based treatments for OCD and PTSD, and more, so we encourage you to check it out !

We also did a talk together at the IOCDF conference in July, 2024 and you can watch Shala’s portion of the presentation in “A new response to trauma and PTOCD.”

When OCD and PTSD Collide | Ep. 362 of Your Anxiety Toolkit

You can listen to Dr. Pinciotti and I discuss more details about the topics above on Your Anxiety Toolkit with Kimberley Quinlan, LMFT

Sources

Fontenelle, L. F., Cocchi, L., Harrison, B. J., Shavitt, R. G., Conceição do Rosário, M., Ferrão, Y. A., & et al. (2012). Towards a post-traumatic subtype of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(2), 377-383. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.12.001

Gershuny, B. S., Baer, L., Parker, H., Gentes, E. L., Infield, A. L., & Jenike, M. A. (2008). Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in treatment‐resistant obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 25(1), 69-71. doi:10.1002/da.20284

Gershuny, B. S., Baer, L., Radomsky, A. S., Wilson, K. A., & Jenike, M. A. (2003). Connections among symptoms of obsessive–compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: a case series. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(9), 1029-1041. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00178-X

Pinciotti, C. M. (2023). Adapting and integrating exposure therapies for obsessive–compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: Translating research into clinical implementation. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000143

Pinciotti, C. M., & Fisher, E. K. (2022). Perceived traumatic and stressful etiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Research Communications, 2(2), 100044. doi: 10.1016/j.psycom.2022.100044

Pinciotti, C. M., Post, L. M., Miron, L. R., Wetterneck, C. T., & Riemann, B. C. (2022). Preliminary evidence for the effectiveness of concurrent exposure and response prevention for OCD and prolonged exposure for PTSD. Journal of Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders, 34, 100742. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2022.100742

Pinciotti, C. M. & Wadsworth, L. P. (2023, July). When OCD and trauma intersect: Preliminary findings from a national study. Paper presented at the 28th annual meeting of the International OCD Foundation, San Francisco, CA.

Van Kirk, N., Fletcher, T. L., Wanner, J. L., Hundt, N., & Teng, E. J. (2018). Implications of comorbid OCD on PTSD treatment: A case study. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 82(4), 344-359. doi:10.1521/bumc.2018.82.4.344

Learn more about taming OCD

To learn more about how the trauma of The Accident impacted my OCD, read or listen to Is Fred in the Refrigerator? Taming OCD and Reclaiming My Life. Click here to purchase a copy.

Sign up for my Shoulders Back! newsletter to receive OCD-taming tips & resources, including notifications of new blog posts, delivered every month to your inbox.

My blogs are not a replacement for therapy, and I encourage all readers who have obsessive compulsive disorder to find a competent ERP therapist. See the IOCDF treatment provider database for a provider near you. And never give up hope, because you can tame OCD and reclaim your life!

Photos of intertwined ropes © Can Stock Photo / grandaded

Wow, this was really interesting. Thanks a lot for sharing this Shala! Greetings from Sweden

Great article. I have ptsd which then manifested into real event OCD. After having been hurt, I hurt others in my life (in a different way than I was hurt but nonetheless I hurt them). Cannot quite forgive myself though I have been forgiven.

Hoping to work with a specialist soon … real event ocd js horrible!

I have PTSD OCD. EMDR has helped a lot with most triggers I’ve had. I’m a believe it probable works similar to PE but with the bilateral stimulation.

Really helpful article. And it was great to listen to Dr. Pinciotti at the Annual OCD Conference in San Francisco last week.